By Katie Cross

Since 2014, we have surveyed undergraduate students at the University of Bristol to help us understand the impact that finances have on the experience of studying at the University. Our latest survey, conducted in May 2021[1], allowed us to ask students about their financial experiences of the 2020-21 academic year, more than a full year after Covid-19 first hit. As part of our survey this year, we incorporated several questions specifically on student accommodation, namely where respondents were living at the time of the survey, whether they had lived anywhere else during term-time, whether they had an adequate provision of study whilst at alternative accommodation and what impact Covid-19 had on their accommodation costs. We also allowed students to comment qualitatively about their accommodation experience.

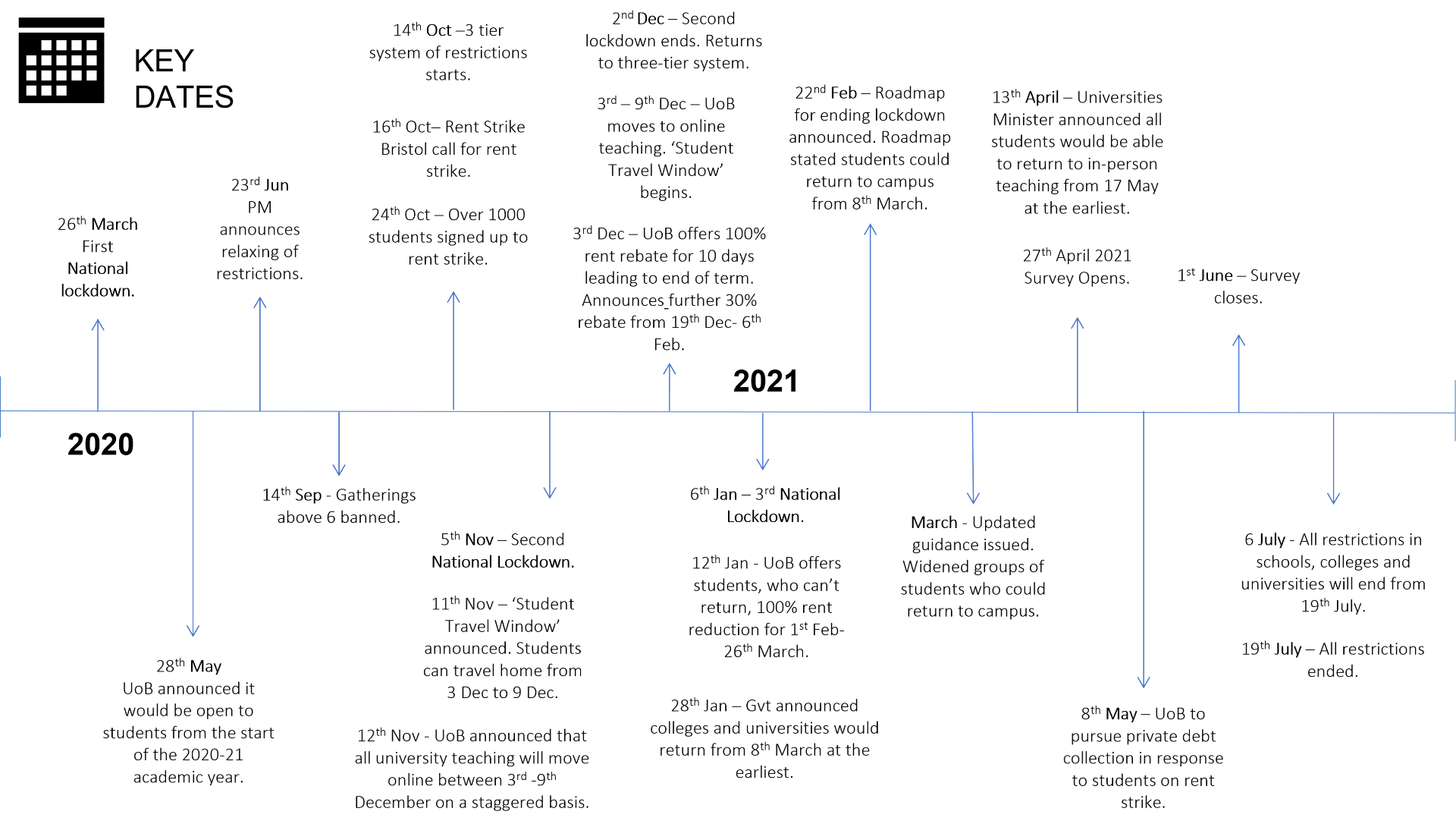

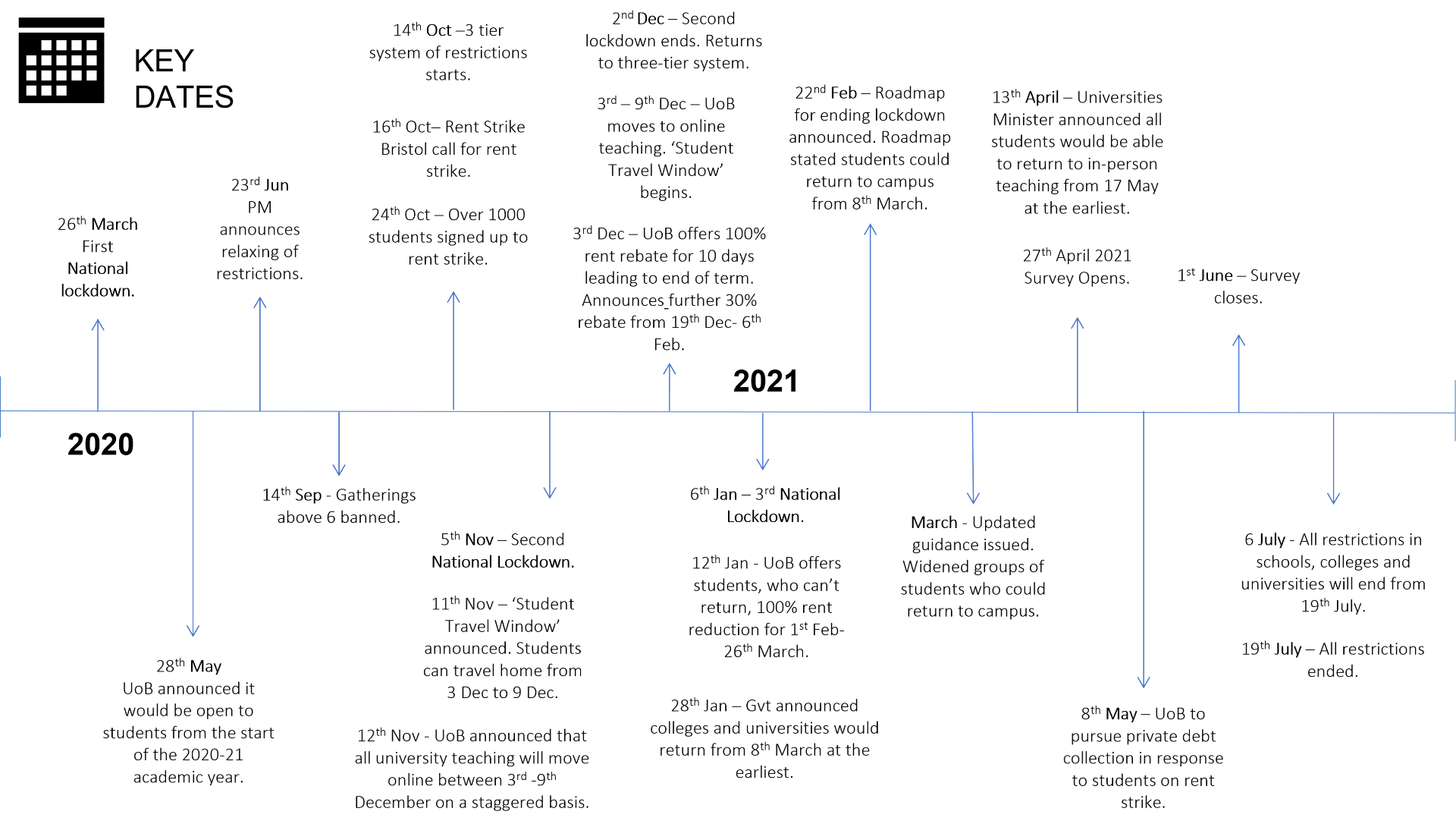

Over the summer of 2020, Covid-19 restrictions were gradually eased: we emerged from the first national lockdown at the end of June with pubs, hairdressers and restaurants reopening in July, and in August, the Eat Out to Help Out scheme was introduced, to encourage us further back into pubs and restaurants[2]. In May 2020[3], the University of Bristol announced that it would be open to students from the start of the 2020-21 academic year, offering a blended approach of campus and online education; large-scale lectures would be moved online but face-to-face small group teaching and mentoring would go ahead.

With that in mind, many students moved to Bristol for the start of the academic year, either for the first time or as returning undergraduates. However, further restrictions on the number of people allowed to mix indoors, along with the national lockdowns in November 2020 and January 2021 meant that much of the 2020-21 academic year was again heavily disrupted for students. Although urged to stay in Bristol until the end of Autumn Term, many students went home before the lockdown restrictions came into force in November. Others locked down at University and waited until the Christmas break to travel home. After Christmas all students were advised not to return for their second term, and the Government announced that in-person teaching would not resume again until the 17th May 2021 at the earliest[4].

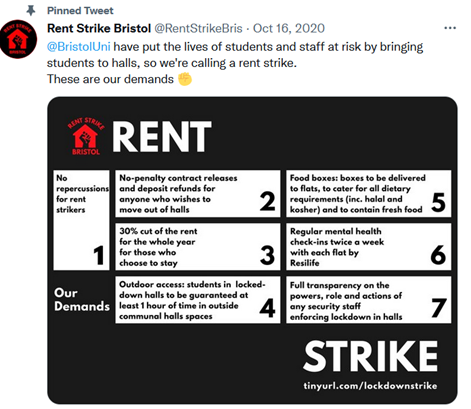

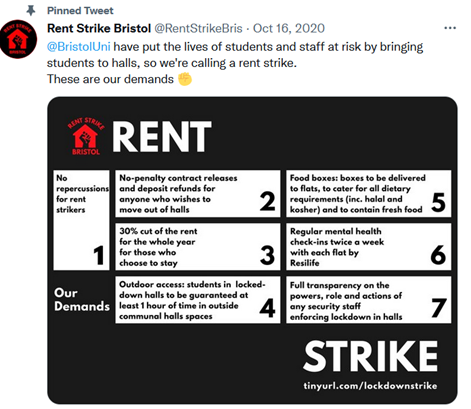

Many were frustrated that they were required to pay for University accommodation that they weren’t living in and even prior to the November national lockdown some students were frustrated by having to self-isolate within halls[5]. Controversy had arisen over the quality of foodboxes provided to students required to self-isolate[6], although some were pleased with what they had received[7]. Many students were also angry at how little face-to-face teaching they were receiving and by the 24th October 2020, over 1,000 Bristol students had signed up to the University of Bristol Rent Strike campaign[8]. The students were calling for rent reductions, no-penalty contract releases and better conditions for those living in halls during lockdown (Figure 1). While some concessions and rebates were won, by May 2021 students and the University of Bristol were still in dispute[9][10][11].

Figure 1: Rent strike Bristol demands

This turbulent year for students has had a real impact on student mental health, which we will explore in a separate blog. Here, we focus specifically on the student experience in relation to their accommodation; patterns of movement and how students felt about living arrangements during 2020-21.

Movement of students

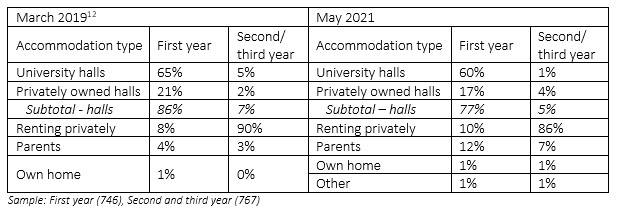

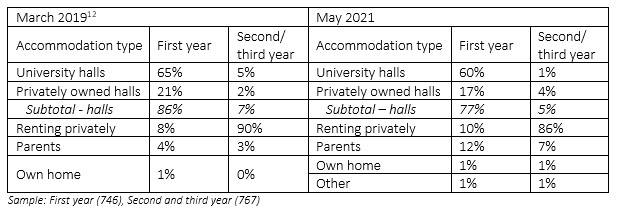

When we ran our survey in May 2021 over three quarters (77%) of first year students were living in halls, 10% were renting privately and 12% were living at home with parents. Second and third year students on the other hand were much more likely to be renting privately (86%), with only 5% in halls and 7% living with parents. The percentage of students in all years living with parents was higher in May 2021 than it had been pre-Covid (Table 1) from our previous annual survey two years before, although still only a minority of students were living at home.

Table 1: Student accommodation type by year group – 2019 vs 2021 (annual survey comparison)

Around half of students reported living in different accommodation at some point during term-time

We asked students whether they had lived anywhere else that academic year during term-time (other than where they were living in May 2021 – when the survey was taken). For instance, this could refer to students who lived in halls before Christmas but were at their parent’s home by May 2021, or those who were living in halls in May but who had moved home to live with parents earlier in the year, e.g. during lockdowns, and then back again to Bristol.

Given the lack of in-person teaching and restrictions, it is perhaps surprising that fewer than half of students overall (48%) reported living in different accommodation at some point that academic year. First year students were significantly less likely (44%) than second and third years (51%) to report moving accommodation during term-time. This is again unexpected, given that first year students were more likely than their second and third year peers to live in University-owned halls, and therefore to be offered some form of rebate (as seen below in Table 2). In contrast, those living in private accommodation were required to negotiate with a range of private landlords for any such rebate. It may be that remaining on campus was more important to first year students, trying to settle in, than those with a year or more to embed themselves in the University student community.

The impact on study provision

Around half of students who moved (47%) reported having inadequate provision for study at their alternative accommodation, with a lack of adequate space (36%) and of adequate broadband connection (26%) being notable issues. Qualitatively, some students reported difficult living conditions at home as a reason for returning to campus despite the lockdown, amid concerns over the potential impact on their academic performance.

- “I live in a basement flat and my room is very small with no natural light. It is depressing and I have nowhere else to work, so my motivation to complete my degree has plummeted. As a third year, I really feel that this has therefore had a substantial impact on my grades. Without a comfortable or acceptable working space it has been a nightmare to concentrate” – Year three female

Many students paid for unused accommodation

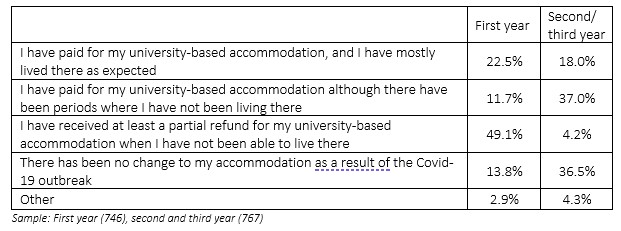

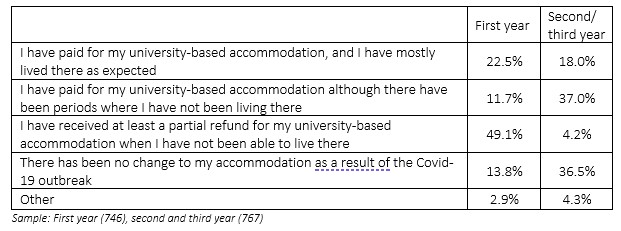

Despite the University offering rebates[13], these were only for those living in halls, so primarily first year students. Unite owned halls also offered rebates to students[14]. However, according to our survey, very few (4%) second and third-year students were offered a refund for their accommodation (Table 2), as they were much more likely to be renting privately (Table 1). Many second- and third-year students reported spending little time, if any, within their Bristol accommodation but still having to pay their rent there in full.

- “I have had to pay for a flat that has gone entirely unused while also paying money to live at home with my parents” – Year three, male

Our research indicated that only around a quarter of students (26%) received some form of refund, while a similar proportion paid for University accommodation in full despite not living there at certain periods (25%)[15]. As mentioned, this varied greatly by year group with nearly half of first year students (49%) receiving some form of refund, compared to only 4% of second and third year students (Table 2). Separate research conducted nationwide by Save the Student, estimated that students spent £1bn in a year on empty accommodation and that the average student spent £1,621 in rent for unrefunded rooms[16].

Table 2: The impact of Covid-19 on accommodation costs (2020-21 academic year)

Uncertainty over level of in-person teaching

Importantly, students may have made different accommodation choices if they had been prewarned clearly how little face-to-face tuition they would receive, difficult though that would have been for the University. Instead, under uncertainty they could respond very differently, as these two responses show.

- “The university told me that it was highly advisable to live in Bristol if possible. So, I’ve ended up paying 12 months rent for flat that I’ve lived in for 3 months” – Year two male

- “Because my course was online for term 2, I was able to go home, save the rent money that can be used for my summer rent at the 2nd year house” – Year one, female student

Lockdown living

Some of those who remained in student accommodation during term-time found it very isolating, and this could have impacted on their mental health. This was particularly true for first year students, who had not yet had the opportunity to build support and friendship networks.

- “I lived on my own for 4 months with no flatmates, in a national lock down. It was not the best experience” – year one female

- “Not been able to meet people outside of my flat really. Very isolating and limited” – year one, female

- “Living in a house of 9 people was very uncomfortable when COVID-19 was extremely prevalent. Due to COVID-19 infections our house had to quarantine for about 3-4 weeks. After being locked in a house with no garden and really poor facilities I travelled home because it was mentally no longer feasible to remain in Bristol” – year two male

Others noted that some of the key social facilities normally offered as part of their accommodation had been closed e.g., common rooms or study rooms, and so felt they had paid for something they didn’t have access to. Some also found that the maintenance of the accommodation was poor, as a result of the Covid rules.

- “It resulted in us paying for facilities (gym; music rooms; common rooms; hall bar; study rooms) that we were promised but have never had access to” – year one, female

Greater financial and emotional support needed for students

Overall, many students understandably expressed their disappointment with their accommodation experience over the past year. It has clearly been difficult for students academically, socially and in terms of mental wellbeing, and it is important that the University listens to and learns from their experiences. Whilst it would have been impossible for any university to know ahead of time precisely how its 2020-21 academic year would play out, there needs to be greater recognition that much of the adversity was borne by students, particularly first years with no prior familiarity with the University or their fellow students, who might reasonably have been expecting a greater duty of care to be shown to them. The pandemic was obviously very unsettling for academic, administrative and support staff as well, but not only did almost all have previous experience of working under lockdown conditions from 2019-20 but also had local homes to work from and supportive local communities, so were not faced with a parallel set of decisions and realities over the upheaval to their Bristol-based accommodation.

With hindsight, greater financial hardship support could have been offered to students who were struggling to pay for their rent; those who couldn’t work as they expected (either in term-time or the holidays) or whose family income had dropped because of the pandemic, for example. And while lockdowns were not within the control of the University, how it communicated with students about these changes was. Some students were left feeling that the University was more concerned with its own finances than with the health and well-being of its students, especially when, in May, 2021, it turned to third party debt collectors in response to the rent strike.

It was a very difficult year for both staff and students at the University, and greater mutual empathy and understanding could have gone a long way in supporting each other in a crisis.

[1] Fieldwork was conducted between 27th April and 1st June 2021.

[2] https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/timeline-lockdown-web.pdf

[3] https://www.bristol.ac.uk/news/2020/may/covid-update-academic-year.html

[4] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-56731330

[5] On the 9th October the University shut “The Courtrooms” residence (which had over 300 students) because 40 students had Covid.

[6] https://epigram.org.uk/2020/10/20/bristol-uni-rent-strike-on-course-to-be-the-biggest-in-uk-history-after-1000-signups/

[7] https://thetab.com/uk/bristol/2020/10/09/uob-freshers-are-being-given-incredibly-posh-food-boxes-full-of-soy-sauce-and-propercorn-42271

[8] https://twitter.com/rentstrikebris

[9] https://www.bristol.ac.uk/accommodation/coronavirus/20-21/rent-rebate/

[10] https://tribunemag.co.uk/2021/01/britains-historic-wave-of-student-rent-strikes

[11] https://epigram.org.uk/2021/05/08/rent-strikers-face-third-party-debt-collection-from-bristol-university/

[12] Questions on student accommodation are asked annually as part of the student survey. March 2019 is the latest survey available prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. The 2020 survey was asked slightly later in the year (May as opposed to March) and so embraced the first lockdown of universities under Covid-19, in late March 2020

[13] https://www.bristol.ac.uk/accommodation/coronavirus/20-21/rent-rebate/

[14] https://epigram.org.uk/2021/03/06/unite-students-announces-a-further-rent-reduction-for-march-2021/

[15] Not all students living in halls would have automatically received a refund. The first two rebates given by the University were automatically provided but students were required to apply for the third rebate by a specified deadline.

[16] https://www.savethestudent.org/accommodation/national-student-accommodation-survey-2021.html

![]()