Sharon Collard, University of Bristol and Jamie Evans, University of Bristol

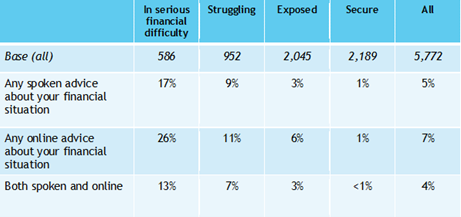

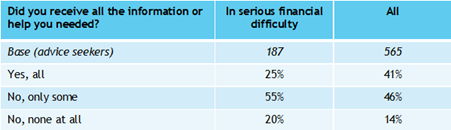

Even before the current cost of living crisis, disabled people were much more likely than non-disabled people to be in poverty and living on inadequate incomes. Now, spiralling living costs are adding to years of financial disadvantage. Our new analysis of YouGov survey data starkly illustrates the situation, showing that three in ten disabled households are in serious financial difficulty.

The UK government has announced several measures that will provide some relief for many, including an energy price freeze and payments totalling £650 for people on means-tested benefits. All households will also receive a £400 reduction in energy bills via instalments spread over six months, and 8 million pensioner households are receiving a separate one-off payment of £300.

Disabled people who receive benefits that aren’t based on income (non-means-tested) will also get a one-off cost of living payment of £150. But while these measures are welcome, this amount is a fraction compared to the additional costs disabled people typically have to cover.

Disabled households often need to spend more on essentials like heating and insurance, as well as necessary equipment, therapies and support. In 2019, disability charity Scope estimated that disabled people in the UK face extra costs of £583 per month, on average. For one fifth of disabled people, this “disability price tag” was over £1,000.

Rising energy costs are particularly impacting households that need to run vital equipment. Wheelchairs, feeding and suction pumps, or ceiling hoists all need to be constantly charged. Some people may also need additional heating to stay warm to prevent pain or seizures.

Considering these already higher costs, it should not come as a surprise that disabled households are disproportionately cutting back or doing without compared with other households. We found that four in ten have cut back on overall spending in 2022, and half have already struggled to keep their home warm this year. Similar proportions have reported reducing their use of the cooker and shower.

Around one in ten non-disabled households report that rising costs mean they are eating fewer meals. This rises to three in ten among disabled households. A survey conducted by the charity Family Fund found that half of carers looking after disabled children have skipped meals in the last year. We increasingly hear about “choosing between heating and eating”, but there are concerning reports of some being forced to choose between heating and medication.

Many disabled households are already at a breaking point, even before we enter a more costly winter. There is nothing else these families can cut back on. The situation is so dire for some that for the first time in its history, the deaf-blind and complex impairments charity Sense is giving cost of living grants of £500 directly to families.

When work and benefits aren’t enough

Soaring inflation means that disabled people in employment are experiencing the same real terms fall in wages as the rest of the working-age population. Around half of working-age disabled people are in work, but many others are excluded from participating in the labour market.

There is a large gap between the rate of disabled and non-disabled people in employment, for many reasons including structural and discriminatory barriers. Disabled people are also underemployed due to the quality of jobs on offer to them, forced to take lower-skilled or lower-paid roles offering fewer or infrequent hours.

Across all UK households in serious financial difficulty, disabled households are much more likely to have no earners than their non-disabled counterparts. But with a quarter of disabled households who have two full-time workers currently in serious financial difficulty, work is by no means a guarantee of avoiding hardship. In-work poverty disproportionately affects disabled people.

Zvone / Shutterstock

Disabled people are more likely to engage with the social security system. This is partly due to their lower employment rate, but also because there are benefits available to assist with the higher cost of living with a disability. State benefits for disabled people rose by 3.1% in April.

But, as is the case with earned income, rising inflation means that benefits are shrinking in real terms. For disabled households, this means substantial monthly financial losses.

Families with a disabled adult were among the hardest hit groups from changes to the social security system in the 2010s, with the inadequacy of provision for disabled people attracting widespread criticism. The process of applying for disability benefits has been described by disability campaigners and charities as complicated and inhumane.

For lower-income disabled households, these new cost of living payments will be insufficient or at best, a short-term solution to longstanding financial inequalities. These disadvantages are more widely corrosive, driving social exclusion, limiting agency and choice, and ultimately impacting people’s mental health and wellbeing.

To meet the scale of the crisis faced by disabled households, longer-term solutions – such as proposals for a decent social security system – are certainly needed if we are to avoid a further decline in living standards.![]()

Sharon Collard, Professor of Personal Finance, University of Bristol and Jamie Evans, Senior Research Associate in personal finance, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.