A message from our Research Co-Directors

This year the Personal Finance Research Centre published 12 new research reports and 5 policy briefings. At the same time, our team have found time to respond to consultations and calls for evidence, write peer-reviewed journal articles, speak at conferences and on radio shows, and lead some of the projects that we’ll be reporting on in 2024.

All of this activity has the common goal of sharing our research as widely as possible and promoting our recommendations for changes to policy and practice that can improve situations for individuals and households.

In 2023, the cost-of-living crisis remained at the top of the policy agenda, and we spent the year researching its impact. Our Financial Fairness Tracker (in partnership with abrdn Financial Fairness Trust) has documented how UK households are coping. The 8th and 9th waves of the Tracker in May and October found ‘a new normal’ where some households are beginning to adjust to higher costs, but their overall financial wellbeing remains significantly worse than in 2020 and 2021. We also investigated the financial wellbeing of disabled people; considered the role that housing tenure plays in household finances; and collected first-hand testimonies from people who struggled with high energy costs last winter. In all our reports, we highlight the real-world implications of our findings and make evidence-based recommendations about how best to support those who need it.

As ever, collaboration has been a fundamental part of our research in 2023 – with other academics and research organisations, policymakers and practitioners, charities and civil society organisations, and – crucially – the lived experience experts and research participants whose views and experiences we seek to accurately represent through our work. Our thanks to everyone we’ve worked with this year.

If you haven’t already done so, we hope you find the time to engage with at least some of our research. And please do get in touch if you have any questions or reflections to share.

Wishing you all the best for the new year.

Sharon Collard and Sara Davies, Research Co-Directors

Research and policy

In 2023 we explored:

- The financial wellbeing of UK households (in ‘The new normal’ and ‘Turning a corner?’). In addition we explored the financial wellbeing of different groups including: Scottish households; different tenure groups; and a major study designed with the help of disabled people people, which explores what ‘financial wellbeing’ means to them and the difficulties they face in trying to improve their financial wellbeing. From this we published four policy briefings on the benefits system; barriers to employment; access to essential services; and the extra costs of disability

- The intersecting impacts of mental ill-health and money problems on the financial wellbeing of people from minoritised ethnic communities.

- The scale and nature of the poverty premium in 2022, building on our 2016 and 2019 research in this area.

- An evaluation of the Nationwide Incubator to tackle the poverty premium that low-income households in the UK face.

- The substantial extra costs and loss of income that can occur as a result of living with Cystic Fibrosis.

- The family dynamics of gambling harms, which highlights the need for strategic efforts to support those affected by someone else’s problem gambling.

- Testimonies from the energy crisis, which foregrounds the lived experiences and behaviour changes made in homes as people sought to reduce their energy bills in the winter of 2022/23. Using interviews and financial diary methods, we sought to understand experiences during the energy crisis, and how current and future policies can provide support.

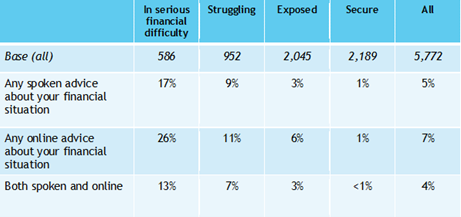

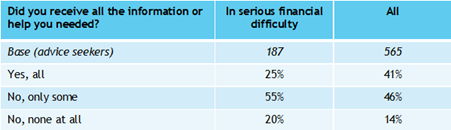

- Supporting debt advice clients through strong referral partnerships

All of these outputs are available on our website.

🎉PFRC at 25🎉: UK Household Finance and Poverty Conference

In November we hosted a one-day in-person conference to celebrate 25 years of PFRC, which was founded in 1998 by Professor Elaine Kempson. The conference agenda centred around three themes:

- Reflections on the past, present and future of household finances through the lens of 25 years of impactful research.

- The seen and unseen dimensions of poverty, with a focus on housing and energy.

- Research into policy and practice.

Attended by over 80 delegates, it was a day of excellent keynote speeches, lively panel discussions and stimulating conversations. It was also a fantastic opportunity to catch up with old friends and colleagues and make new connections. Our thanks to everyone who joined us and helped make it such a great day.

Want to keep up-to-date with our latest research? Join our mailing list