By Sharon Collard

Please note: This blog discusses harmful gambling and its impacts.

In July 2023, a team from the Personal Finance Research Centre, FinTech West and the lived experience-led charity Gambling Harm UK delivered a workshop to consider how FinTech can help reduce harm from gambling. This was a great example of ‘grounded innovation’ in action: bringing FinTechs together with people who have lived experience of gambling harms to focus on real-life issues and how to solve them.

It highlighted useful products and services that FinTech firms already offer as well as opportunities for further innovation. Most of all, it showed the invaluable contribution that experts-by-experience like Gambling Harm UK bring to the table.

We are grateful to Higher Education Innovation Funding for funding the workshop.

Helping FinTechs understand the harms caused by gambling problems

A key part of the workshop was Chris Gilham, Julie Martin and John Gilham from Gambling Harm UK sharing their own personal experiences, which illustrated the complex and messy nature of gambling problems and their serious long-term impacts.

Chris told us about having been diagnosed with Adult ADHD just over eighteen months ago at almost 40 years of age, and how he has battled with his mental health since his mid-teens and using alcohol to cope. Then when he was 30 years old, having had no previous interest in gambling, he saw an advert and that day, he decided to try it. He explained that whilst gambling initially made him feel calmer, it wasn’t long before he was suffering from gambling harm. After almost five years of harm he finally found recovery following a two-day gambling binge, when he was planning to win and leave money to his family before ending his own life. Julie described the severe financial toll that her ex-husband’s gambling had on her and her children, meaning she had to work four jobs just to pay off loans he had taken out in her name, as well as the verbal, mental and sometimes physical abuse that she experienced. John (Chris’s dad) told us about his experiences as the parent of someone with a gambling addiction, how his life and that of his wife and family had been turned upside down and his role now supporting Chris in his recovery journey, including helping Chris keep tight control of his money.

These real-life experiences really resonated with workshop participants – even if they had no experience of gambling harms. Our rich discussion touched on many issues including the links between ADHD and impulse behaviours such as gambling; the fact that there is no single reason for gambling problems; and the normalisation of gambling-like behaviours in online games that are so popular among children and young people, through features like microtransactions and loot boxes that are played to get an edge. John reminded us that 55,000 young people aged 11-16 in Britain are categorised as ‘problem’ gamblers – a term which stigmatises those suffering from this illness – with a further 85,000 young people estimated to be at risk of harm from gambling.

How FinTechs can help reduce harms from gambling

There is no perfect solution to help someone control their gambling. Blocks, self-exclusion schemes and other features can all be circumvented if gambling has become the most important activity in someone’s life and dominates their thinking, feelings, and behaviour. Nonetheless, the workshop highlighted a whole range of things that FinTechs are already doing as well as challenges still to be solved, such as joint accounts that give more control and protection. It also illustrated the invaluable contribution that experts-by-experience like Gambling Harm UK can bring to the table in terms of product ideation, design, and testing.

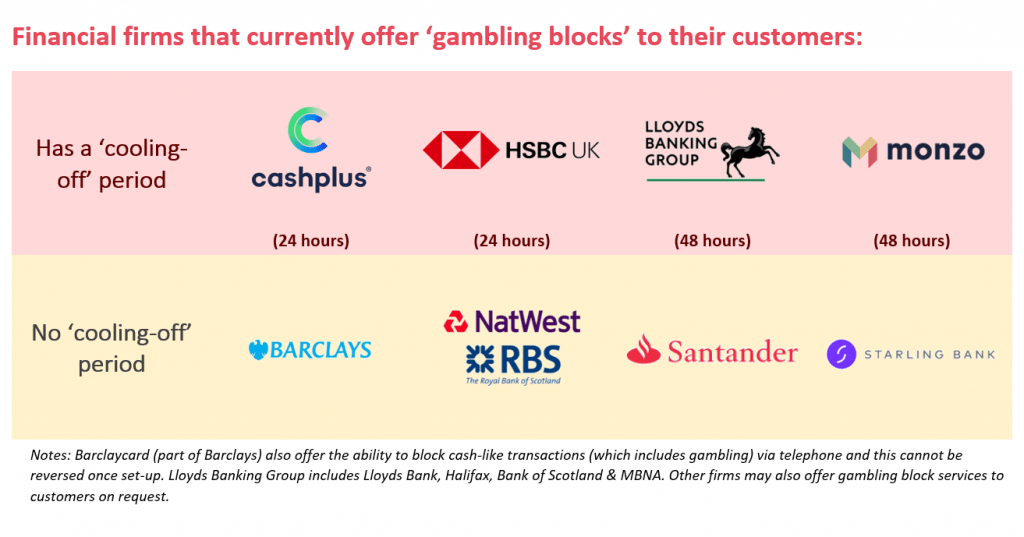

Data-driven early intervention: Starling Bank described how it had a specialist team that proactively contacted loan customers to offer help where their underwriting team identified potential harm from gambling (or where they were in other potentially vulnerable situations), including links to external sources of support. It accepted that the message won’t always land well with customers but in its experience, there was more positive than negative feedback from customers. Saying the right things, in the right way is key, which Chris, Julie and Julie all confirmed was so important, means testing the language and training staff. Indicators of potentially harmful gambling might include applying for large loans late at night and multiple gambling transactions across several sites in a very short space of time.

Enhanced friction and control features: At a time when it is quicker and easier than ever to set up a new bank account or take out a sizable loan, there is significant potential to give customers more control over their spending from the get-go. This might be a bank account where you have to opt-in to be able to gamble rather than opting out; or a non-gambling banking app with enhanced transaction monitoring. Through its personal financial management features, Moneyhub enables its users to set up spending flags across multiple accounts, making it easier for people to see what they are spending on different expenditure categories (such as gambling) where they may want to exercise more control and set spend limits. As Chris attested from his personal experience, tools to help people set up, and stick to, a budget can be an invaluable part of someone’s recovery from gambling addiction, ideally with a human element as well.

Joint accounts: As an affected other, Julie highlighted the problems that resulted from having a joint account with her then-husband. He took her earnings and their savings from the joint account to gamble leaving her in dire financial straits, but Julie was unable to close the account without his permission. While joint accounts nowadays offer both parties easier visibility of the account data, for example via banking apps, in practice there may not be equal access or control if one partner is the victim of coercive control or financial abuse. Other research has highlighted the potential for a safer joint account using Open Banking payment initiation, but while the technology exists to build such a product, it is not yet available.

Help to rebuild finances in recovery: John wanted to see financial services do more to support people with gambling problems to achieve sustainable recovery, by helping them rebuild their finances and their credit rating. Partly this is about raising awareness among FinTechs and other financial firms that gambling addiction is an impulse control disorder; and that people in recovery may be returning to a life they need help to cope with.

In practical terms, it is about helping people build their finances so they can rebuild their lives, for example offering lower interest rates to people who have shown they can stick to a loan repayment schedule; allowing people to pay back debt over longer periods without penalising them; providing money management features such as ‘account sweeping’ to help repay debt or to start saving.

Make gambling harms a normal thing to talk about: making it normal for us to talk about gambling harms and their potentially devastating impacts makes a lot of sense, given that millions of people in the UK are affected – not just the person who gambles but those around them as well. And taking the conversation to FinTechs and other financial services firms has the potential to stimulate even greater innovation for good.

“Thank you so much for speaking to us in Bristol today. You really brought home how important it is for financial service providers to engage and to think bigger and better about how we can prevent and reduce harm and aid recovery. And for me most importantly, some immediately actionable insights which we can do something to address now in our own lending practices. Every step in the right direction, however, small, is very valuable in making change.” James Berry CEO, Great Western Credit Union.

“Thank you for organising such a fascinating yet poignant discussion. Matthew Barr, John Dyer and I left energised planning how we at Moneyhub can do more to support those affected by gambling harm and how financial institutions can position themselves as a first line of defence to protect those who are vulnerable.” Jonathan Bell, Sales Director (Decisioning), Moneyhub.

If you have been affected by any of the issues in this blog, you can contact the National Gambling Helpline which provides confidential advice, information and support by telephone and webchat free of charge.

To find out more about the work of Gambling Harm UK, please contact John Gilham, CEO: john@gamharm.co.uk