By David Collings and Sara Davies

Over 14 million people in the UK population live in poverty, and many more live on low incomes. Unfair poverty premiums – the additional costs people on low incomes incur when paying for essential goods and services – put undue strain on the household budgets that can least afford it, locking people into cycles of poverty. Since we published our 2016 research, the nature of the poverty premium may have changed but it certainly hasn’t gone away. And according to our latest research for Fair By Design and Turn2Us, a national charity providing practical help to people struggling financially, people already struggling financially are paying almost £500 more for essentials like energy, credit and insurance.

The average premium is almost £500, and reflects the current market and regulatory landscape

In 2019, Fair By Design and Turn2US asked us to explore recent changes to the poverty premium landscape – including both regulatory and technological changes – to understand if they are having an impact on the cost of poverty premiums or the number of people paying them. To do this we surveyed 1,000 people living in low-income households who had contacted Turn2Us for help. Our research showed that low-income households incur an average £478 of extra costs through energy, insurance, and credit poverty premiums:

- Car insurance was the biggest contributor to the premium in 2019 at nearly £500 – some pay nearly £300 more per year because they live in a deprived area, and additional charges for paying monthly instead of annually could add a further £160. This premium is markedly higher than it was in 2016, when together these cost an extra £155.

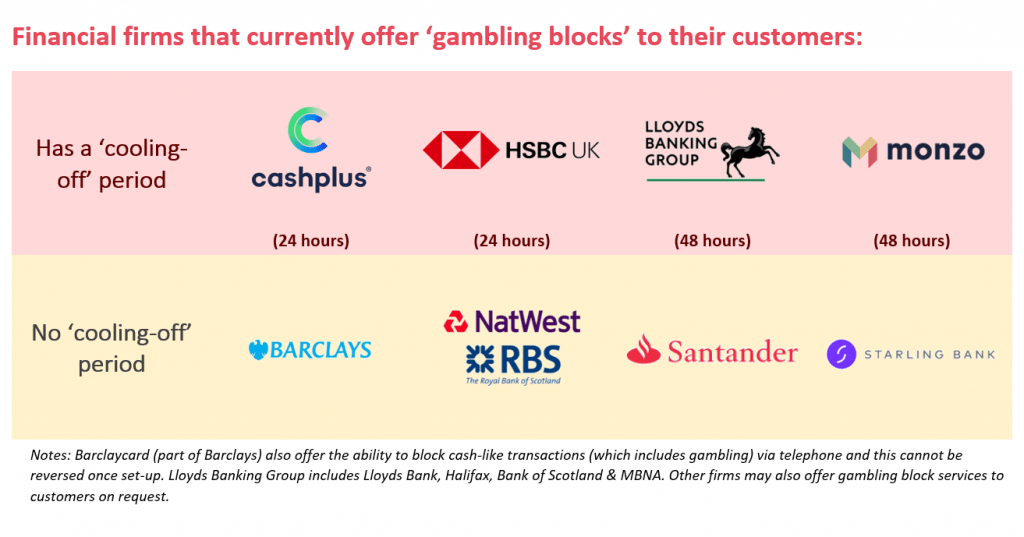

- Credit is particularly expensive on a low income, in whatever form it takes. For example, a sub-prime credit card costs around £200 more per year on average, and personal loans cost more than £500 extra.

- And we found similar inequalities in relation to energy; the best prepayment tariff could still be around £130 more expensive than the best online-only deal, and paying on receipt of bill could cost an additional £143 more per year. However, the drop in the premiums incurred via energy costs since 2016 suggests that the tariff caps implemented by Ofgem have had a positive effect.

Of course, while £478 is the average premium, there is no such thing as an average low-income household. The extent and experience of the poverty premium varies widely between groups and families.

Unfair poverty premiums are yet another example of the inequality of poverty

Our research was undertaken in late 2019, before the onset of the pandemic. However, recent evidence shows that the economic and social consequences of Covid-19 are being felt most keenly by those on low incomes, with lower-paid workers more likely to have been furloughed or to have lost their jobs. Coping with tough times is hard enough when approached from a generally constrained financial position, but the finances of low-income households had already been worsening in the years leading up to 2020 – real income growth stalled in 2017-18, something that affected the poorest the most. And the social safety net had been badly damaged, with cuts to working-age benefits and tax credits further pushing down the incomes of low-income households. Seen in this context, poverty premiums are yet another example of the inequality of poverty, compounding and extending hardship at a time when increasing numbers are experiencing major falls in income, perhaps tipping people over from just about managing to not managing.

What happens next?

We can be certain that the pandemic’s economic impacts are with us for the foreseeable future. But while much in 2020 remains outside of our control, the poverty premium was and remains a solvable problem. Regulators and policymakers should now work together to find solutions for people struggling across all markets. In recent years we’ve already seen the positive impact of such interventions, most notably in the form of price caps. So what more can we do now?

We’ll leave the last word to Jamie Greer of Turn2Us:

“Stronger regulation of financial products, an improved social security net with crisis grants and protective changes to the energy market would mean we can start eradicating the poverty premium.”

Read the report and executive summary