By Jamie Evans

In what many will consider a somewhat worrying sign of the times, in the UK, job adverts for debt collectors surged in August. This comes after news that during and following lockdown, households receiving financial support from the Government were increasingly likely to have missed debt repayments or fallen behind on household bills.

Where the UK’s economy heads next is something that will cause concern for many of us. Financial difficulty and, in particular, debt can be a major source of stress and poor mental health – and can also impact on numerous other aspects of our lives, including our relationships and productivity at work.

But, while debt itself can be problematic, the actions of creditors when collecting money owed to them are just as – if not more – important. Where good debt collection practices will hopefully help the debtor find a route out of difficulty, poor practices will simply make problems worse.

Government debt collection practices ‘worst in class’

As I outlined in a new briefing paper for the House of Commons Library, the debt collection practices of central and local public sector bodies have increasingly been called into question in recent years. There are reported to be as many as 500 different public bodies that an individual might owe money to, including the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC), the NHS, and local authorities.

In 2019/20, public sector bodies were owed an estimated £16 billion across several types of debt – including benefit overpayments, council tax arrears, benefit advances, criminal court financial impositions, and rent arrears on local authority housing. The total value of all debt owed to the public sector, however, is not currently measured.

While commercial lenders and debt collectors have begun to improve debt collection practices in recent years – mainly as a result of regulatory action from the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) –government bodies have been heavily criticised for not following suit.

Debt advice charities, including Citizens Advice, StepChange and the Money Advice Trust, have all called on the Government to improve practices – and their calls have been echoed more recently by the Centre for Social Justice and a growing number of MPs and Peers. In 2018, the Treasury Select Committee concluded that public bodies are “often found to be the most zealous and unsympathetic of creditors in collecting arrears” and more recently former Conservative MP Nicky Morgan (now Baroness of Cotes) wrote the following:

“Regrettably, the public sector continues to lag behind. Despite glimmers of progress, the Committee’s verdict in 2018 that the public sector was ‘worst in class’ for debt collection remains sadly accurate.”

Aggressive practices causing downstream problems

Criticisms of the public sector’s approach to debt collection have focused on their perceived heavy-handed nature, with a reliance on enforcement agents (bailiffs), rapid escalation of debts (including the use of imprisonment for non-payment of council tax debt), and increasingly aggressive practices as the financial year-end approaches.

Overall, it is argued that a short-term incentive to collect money owed as fast as possible may come at the cost of longer-term sustainability and may in fact lead to a lower likelihood of all money being recovered or of individuals being able to escape the cycle of problem debt.

These issues are exemplified by the BBC’s docudrama ‘Killed by my debt’, which tells the real-life story of 19-year old courier Jerome Rogers who found himself in debt to Camden Council as a result of two minor traffic violations. In 2016, after the two initial £65 fines he received spiralled to a £1,000 debt and bailiffs clamped his motorbike – his primary means of making a living – Jerome sadly took his own life.

Jerome’s case raised awareness of the issues associated with debt collection and prompted Camden Council (and others) to introduce formal policies related to the treatment of vulnerable debtors. Nevertheless, according to Freedom of Information (FOI) requests made by the Money Advice Trust, in 2018-19, English and Welsh local authorities used bailiffs 1.1 million times to collect council tax debts and 780,000 times for parking debts.

Important geographical differences

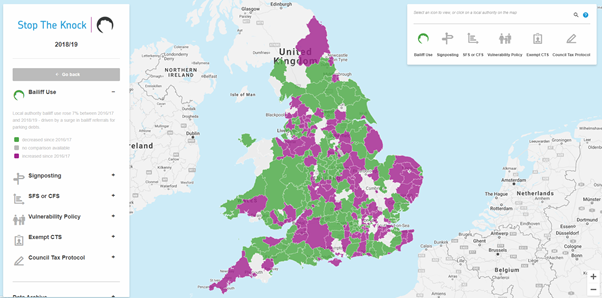

The aforementioned FOI requests also highlight the variation in practices across the country, with bailiff use increasing in some areas but not in others and some local authorities adopting ‘good practice’ measures (such as policies for supporting vulnerable individuals). The Money Advice Trust have mapped these practices across England and Wales, as shown below.

Differences also exist between the constituent nations of the UK. England, for example, remains the only country in UK (and, more widely, in Europe) to imprison people for non-payment of council tax. Wales abolished this practice from April 2019, with Mark Drakeford describing the sanction of imprisonment as ‘an outdated and disproportionate response to a civil debt issue’. Scotland and Northern Ireland also have very different rules around the enforcement of debts more generally.

Recommendations for change

While the Government has already made some changes in this area, including reforms to the bailiff industry in 2014, it recognises that more can be done. In June 2020 the Cabinet Office published a consultation on fairness in Government debt management.

Campaigners argue that the Government needs go much further. In particular, there have been calls for independent bailiff regulation and an end to the practice of imprisonment for non-payment of council tax, as England is the only remaining country in Europe to continue using this type of enforcement. Campaigners also want to end rules which make individuals liable for an entire year’s council tax payments after just one missed instalment, as this fails to offer those having repayment difficulties a route out of debt.

Additionally, a group of 55 cross-party peers and MPs have written a letter to support the idea of a ‘Government Debt Management Bill’. This would place current codes of practice on a statutory footing and more generally ensure consistency across public bodies (and across the country) in the way that they calculate repayment affordability and treat those in vulnerable situations.

With the impact of the pandemic potentially leading to an increase in those facing financial difficulties, such calls for change are only likely to grow louder.

About the Author: Jamie Evans is a Senior Research Associate at the Personal Finance Research Centre, within Bristol’s School of Geographical Sciences. He is currently on a part-time Parliamentary Academic Fellowship at the House of Commons Library within the Business and Transport team. For more information on these fellowships, please visit UK Parliament’s website.

Suggested further reading

Evans, J. (2020) Debts to public bodies: are Government debt collection practices outdated?. House of Commons Library briefing paper number 9007. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9007/

Evans, J., Fitch, C., Collard, S., & Henderson, C. (2018) Mental health and debt collection: a story of progress? Exploring changes in debt collectors’ attitudes and practices when working with customers with mental health problems, 2010–2016. Journal of Mental Health, 27(6): 496-503. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1466040

Anderson, B, Langley, P, Ash, J, Gordon, R. (2020). Affective life and cultural economy: Payday loans and the everyday space‐times of credit‐debt in the UK. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 45: 420– 433. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12355

García‐Lamarca, M. and Kaika, M. (2016), ‘Mortgaged lives’: the biopolitics of debt and housing financialisation. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41: 313-327. doi:10.1111/tran.12126