By Jamie Evans

In recent weeks, debate has been raging about the provision of face-to-face debt advice services in England. Over 1,700 people – many of whom are frontline debt advisers – have signed a petition calling for ‘an immediate pause to the Money and Pensions Service (MaPS) recommissioning of debt advice’, which the authors of the petition, the Unite Debt Advice Network, argue ‘is likely to result in cuts to funding for debt advice of up to 50%, with face-to-face debt advice particularly affected’.

MaPS, on the other hand, believes that its recommissioning exercise ‘will increase the amount of debt advice available to people in England’ and will ‘ensure services are built around customers’ needs’. It says that it has not commissioned based on channel, instead asking debt advice providers to suggest how best to meet the needs of clients using a range of different channels (including but not limited to telephony, face-to-face, virtual appointments, and webchat). In a recent meeting with We Are Debt Advisers (a network of 500 frontline debt advisers), Caroline Siarkiewicz (MaPS Chief Executive) intimated that face-to-face advice would receive 20% of the total funding allocation. We Are Debt Advisers estimates that this would be equivalent to a 16% cut in funding for face-to-face advice services.

The issue has attracted national attention, leading to a Westminster Hall debate on 1st December. A number of MPs advocated passionately for protecting face-to-face services, with Emma Hardy (MP for Kingston Upon Hull West and Hessle) arguing that ‘face-to-face advice is the only way of supporting a significant proportion of people in debt, and… a reduction in capacity and coverage will fail some of the most vulnerable in our society.’

Advisers know channel matters a lot for vulnerable clients

It certainly shouldn’t be controversial to say that different people have different needs when seeking support – whether with debt problems or any other issue they face. This means that some people will prefer digital methods of communication, others will prefer (or only be able to access) more traditional methods, and some might be perfectly happy with a combination of both.

This is something that debt advisers are well aware of.

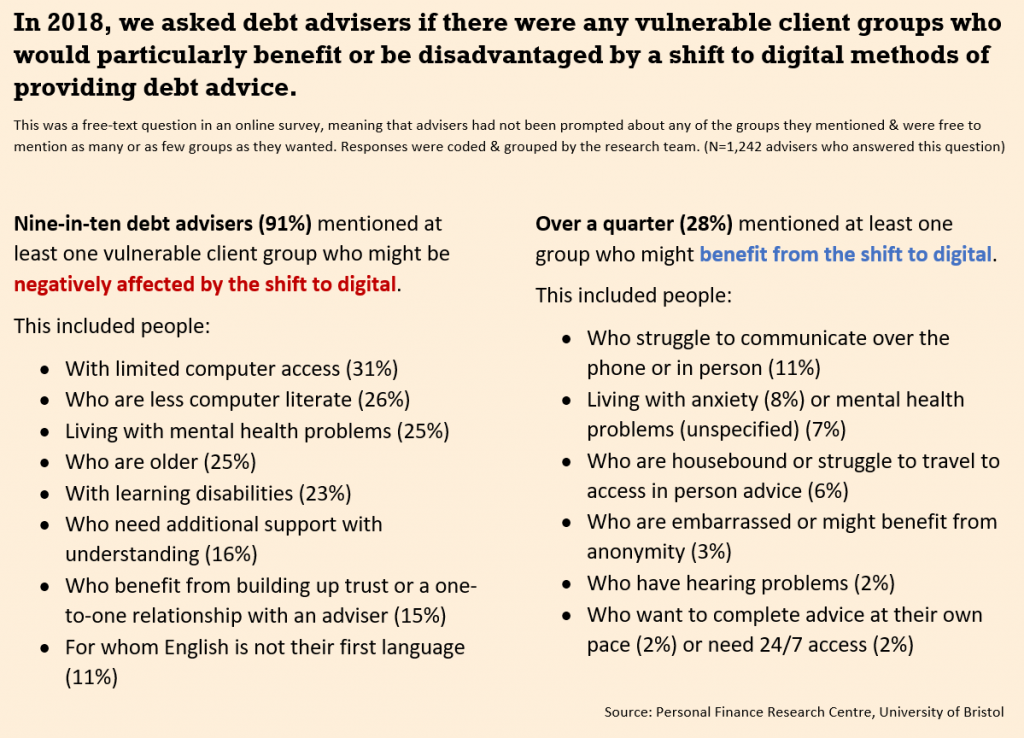

In 2018, the Personal Finance Research Centre received grant funding from the then Money Advice Service to conduct research on debt advisers’ experiences of working with and supporting clients in vulnerable situations – including mental health problems, addictions and a range of other situations. We surveyed more than 1,500 advisers and, as part of the research, we asked if there were particular groups of clients who might be affected (negatively or positively) by a shift to digital debt advice services. What advisers told us is summarised below:

The results demonstrate widespread concern among frontline debt advisers about the potential impact on vulnerable clients of a shift to digital methods of debt advice. They highlighted a range of practical issues that their clients might face in accessing digital debt advice:

“Many of the people I see can’t maintain the same phone number because they can’t afford ongoing phone contracts.”

“Vulnerable clients benefit from building up a relationship with the advisor to be able to trust them enough act on the advice – which they could never get via digital delivery.”

“Clients who can’t afford to eat can’t afford internet… or [can’t afford the] fares to get to free internet.”

“[Face-to-face] we are better able to gauge their needs and abilities, e.g. via email a client can agree to carry out an action but face-to-face we can see that this causes them distress so we can support them to do it.”

Advisers reported that clients with mental health problems, cognitive impairments or learning disabilities may need information explained several times or in different ways. Advisers also highlighted the considerable challenges that clients can face in gathering or understanding paperwork, which are often dealt with quickest in-person.

The scale of vulnerability in debt advice

There are almost always pros and cons to the introduction of new technologies, as we see in long-running debates on issues like access to cash and bank branch closures. Debt advice faces many of the same fundamental questions – but a big difference is the scale of vulnerability encountered by debt advisers.

Based on our survey, we estimate that just under a third of the clients supported by advisers remotely (i.e. telephony or webchat) had disclosed a mental health problem. This rises to half of clients supported by face-to-face advice. In the Westminster Hall debate it was reported that this may rise to as much as 82% for some advisers.

Of course, not all mental health problems are necessarily incompatible with digital advice delivery. Indeed, many people with conditions like social anxiety might be unable to access advice in-person or over the phone, so methods such as webchat offer a hugely important lifeline (see, for example, research from the Money and Mental Health Policy Institute).

Getting the balance right

Getting the balance right requires a comprehensive understanding of demand for debt advice via different channels (including how well demand is actually being met at the moment). This is no easy feat, particularly when we have insufficient data on what the whole debt advice sector actually looks like. Investment to build this data would greatly improve MaPS’ ability to forecast accurately and might improve their chances of obtaining a more representative sample when consulting with advisers from different parts of the sector. It is also important to ensure research on these topics properly involves those who are digitally excluded. This is something we can all improve on.

In the meantime, it would be good to see the evidence on which decisions are currently based. MaPS is yet to publish its formal Equalities and Vulnerability Impact Assessment, so this seems a good place to start.

There are elements of MaPS’ proposals which are (hopefully) welcome from the perspective of vulnerable clients. Caroline Siarkiewicz describes how MaPS hope the new funding approach will get advisers off the ‘hamster wheel’ of dealing with one client after another, leading to more time spent with individual clients rather than simply chasing high volumes.

Whatever happens, it is clear that at present many advisers are suffering poor wellbeing due to their workload – a recent IMA survey found that 68% of those working for MaPS-funded advice organisations were dissatisfied with their workload, with two-in-five (41%) reporting that they ‘often feel stressed and anxious at work’. Many are uncertain about their future and are tired of repeating the same things over and over again, both in relation to debt advice and in terms of wider social policy. They are the experts in this arena, so decision-makers need to start listening.

Read the research here: Vulnerability: the experience of debt advisers