By Sharon Collard and Jamie Evans

Two years on from the start of the Coronavirus pandemic, at least 8.5 million people in the UK need debt advice from a regulated provider, fuelled by a cost of living crisis that is stretching the finances of millions of UK households to breaking point. Even so, our research suggests that only a minority of people who would benefit from debt advice will actually seek it – a conundrum that has exercised the debt advice sector, creditors, regulators and governments for decades. Where people do seek debt advice, the evidence shows that only a minority get all the information or help they feel they need.

The Coronavirus Financial Impact Tracker was commissioned by abrdn Financial Fairness Trust in March 2020 to capture the financial impact of pandemic on UK households through a series of periodic cross-sectional online surveys conducted by YouGov and analysed by the University of Bristol’s Personal Finance Research Centre. Five surveys were conducted over the course of the pandemic, the last one in October 2021.

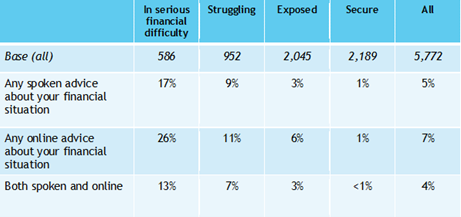

One of the things the surveys ask about is whether people sought debt advice from any free-to-use debt advice providers (such as Citizens Advice, National Debtline, StepChange Debt Charity) or fee-charging companies. Looking at the survey findings from October 2021, we see that only 5% of UK households said they had received any spoken advice about their financial situation since the start of the pandemic; 7% had received online advice (e.g. via by WhatsApp or webchat); and 4% had received both spoken and online advice (Table 1).

Not surprisingly, households in worse financial situations were more likely to have received advice over that period – 17% of households classed as ‘in serious financial difficulty’ had received spoken advice; 26% had received online advice and 13% had received both spoken and online advice (Table 1). That still means most households ‘in serious financial difficulty’ did not get any information or help about their financial situation from a debt advice provider, even though 93% of them said thinking about their financial situation made them anxious, 85% were struggling to pay for food and/or bills, and 55% were in arrears on at least one bill/credit commitment.

It could be that government financial support and payment deferrals from lenders helped many of these households weather the financial impact of the pandemic, but such assistance is unlikely to have resolved underlying debt problems. They may also have relied on self-help and obtained the information they needed from other sources that we did not ask about in the survey.

Table 1

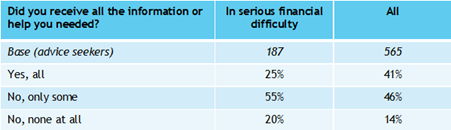

We also asked advice-seekers whether they received all the information or help they needed from the debt advice provider they contacted. Almost half (46%) of all advice-seekers said they only received some of the information or help they needed; and a further 14% said they received none. This picture was amplified among advice-seekers who were ‘in serious financial difficulty’, where only a quarter (25%) said they received all the information or help they needed (Table 2).

Table 2

These findings raise some fundamental questions about why people aren’t seeking help who seem to need it; but also why most advice seekers are not getting all the information or help they feel they need – particularly those ‘in serious financial difficulty’.

Despite all the positive help that debt advice agencies provide, there are limits to what can be achieved for people in serious difficulties who have little or no spare income to pay back what they owe and for whom bankruptcy or debt relief fees may be prohibitive. In some cases, debt advisers may be able to do no more than confirm there is no real tangible help available or any recourse to additional financial support. This points to the need for wider reforms outside the debt advice sector such as adequate state safety nets, real living wages and better access to debt relief.

In addition, advice-seekers may need other services such as welfare benefits advice or legal help with their debts that debt advice services can’t offer. It could also be the case that people have expectations of debt advice services that exceed the reality of what these services can offer. Addressing these questions is important to ensure that debt advice reaches more people who need it and delivers good outcomes for the people who use it.